In “Deadpool & Wolverine,” the first half of that duo (Ryan Reynolds) jokes that the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s “Multiverse Saga” isn’t really working. Does that mean Marvel Studios is switching course? Probably not, if the forthcoming “Avengers: Secret Wars” is any indication.

The MCU has largely been using the concept of infinite worlds as metatext about different superhero movie franchises. “Deadpool & Wolverine” is about how Deadpool wants to be a hero worthy of the Avengers — a transparent representation of how Disney acquired Wade’s previous owner, 20th Century Fox. Sony’s “Spider-Verse” films are at least a tad more creative, using different universes to represent different animation styles.

As a comic fan, it’s a bit surprising that Marvel has embraced the multiverse. That storytelling device has always been more DC’s thing, going back to 1961’s “The Flash of Two Worlds” (written by Gardner Fox with suggestions from DC editor Julius Schwartz, drawn by Carmine Infantino). There is one exception to that rule: the X-Men, who traverse across alternate timelines and dystopian futures all the time. Some of the team — like Bishop, Cable, and Rachel Summers — are refugees from such alternate futures. “Deadpool & Wolverine” follows this tradition.

This goes back to the 1981 story “Days of Future Past” (by Chris Claremont and John Byrne). The robotic Sentinels rule a barren America with mutants herded into concentration camps, so Kate Pryde travels back in time to prevent that world from ever existing. “Days of Future Past” was a mere two issues, but it’s one of the most revisited X-Men stories ever.

One of the most underrated revisits is 2011’s “Age of X,” written by Mike Carey, and drawn by Clay Mann and Steve Kurth in alternating order. The arc appears to be just another “mutants fighting in a dystopia” story, but then it cracks form and a mystery pops out.

Mike Carey’s underrated X-Men legacy at Marvel Comics

Mike Carey is a writer in the mold of Alan Moore and Garth Ennis: born in Britain, he first came to prominence writing American comics for DC. (Carey wrote the “Sandman” spin-off “Lucifer” from 2000 to 2006.) Carey mostly writes novels these days, sometimes credited as “M. R. Carey,” but he spent 2006 until 2012 immersed in the X-Men. He wrote, for my money, one of the quietly best and most influential runs on the title.

Carey’s “X-Men” is cleanly divided into three parts. His initial run is “X-Men” #188-207; the issues were primarily drawn by either artists Chris Bachalo or Humberto Ramos. (Clayton Henry also filled in on issue #191.) This portion centers on Rogue, recruited by Cyclops to assemble and lead a strike team of X-Men. Rogue picks a combination of fellow mavericks (Iceman, Cannonball, Cable, and the Omega Sentinel) and some villains (Mystique, Sabretooth, and Lady Mastermind). These villains aren’t reformed, but they are pursuing amnesty and Rogue wants to keep an eye on them. Carey, an admitted “X-Men” fan who loves how vast the cast is, chose a team full of “internal contradictions” that seemed ripe to “implode.”

After the crossover event “Messiah Complex,” the book was rebranded as “X-Men: Legacy” and shifted focus to Professor X. These two changes aren’t coincidental; these issues followed Charles, now an outcast while the X-Men were led by Cyclops, tending to and paying off old debts. The book was about Charles Xavier shaping and observing his legacy.

For the third part, the book goes back to Rogue. There’s a clean hand-off in the arc “Salvage” (“X-Men: Legacy” #219-225), where Xavier and Gambit track down Rogue in the Australian outback. For his last amends-making, Xavier helps Rogue control her powers, finally fulfilling a promise he made when she first joined the X-Men.

What happens during the X-Men’s Age of X

“Age of X” unfolds during the third and final chapter of Carey’s “X-Men” run. It’s a small crossover event, so it happens in this order:

1. “Age of X: Alpha” #1

2. “X-Men: Legacy” #245

3. “New Mutants” #22

4. “X-Men: Legacy” #246

5. “New Mutants” #23

6. “X-Men: Legacy” #247

7. “New Mutants” #24

8. “X-Men: Legacy” #248-249 (epilogue)

9. Two-part spin-off “Age of X: Universe” by Simon Spurrier and Khoi Pham (non-essential).

Clay Mann drew the “Legacy” issues, Steve Kurth drew the “New Mutants” ones. “Age of X” is not a sprawling mess like most comic crossovers are, though, I promise. Every issue was written by Carey and they flow with a single core cast and throughline. As Carey told the Xavier Files podcast, he initially pitched “Age of X” as just a three-issue arc of “X-Men: Legacy,” but editorial thought it needed to be bigger. So, Carey was given three issues of “New Mutants” to use.

The story takes place in an alternate timeline where the X-Men never existed and mutants have been hunted to near extinction. The last mutants are led by Magneto and based in “Fortress X.” Everyday, they fight off an encroaching army of humans; when “Age of X” begins, the mutants have been under siege for 1000 days. A team of telekinetics, “The Force Warriors” led by Legion/David Haller, are responsible for reconstructing the Fortress’ defenses every day.

Some familiar characters are quite different. Scott Summers is known not as Cyclops, but “Basilisk,” another mythological creature with a deadly eye. Rogue is instead called “Legacy” because of her duty to her endangered species. When a mutant dies, she absorbs their memories and powers, carrying that mutant’s legacy inside her.

But something’s off…

Age of X flips the superhero multiverse concept on its head

In the “Age of X” world, there are no psychic mutants. But how does that account for Legion? If you watched the “Legion” TV series (where David was played by king of onscreen weirdos Dan Stevens), you’ll know that he is the son of Charles Xavier. His psychic powers are coupled with multiple personalities, leaving him an unstable force.

Rogue/Legacy, Gambit, and Magneto do some digging and find many psychic mutants locked in the basement of Fortress X (among them is Charles Xavier, who none of them know). No world exists beyond the Fortress either, but then where do the human soldiers come from? And what role does Legion’s stepmother, Moira MacTaggert, have to play?

Once Charles wakes up, he reveals the truth. “Age of X” is not happening in an alternate timeline — it’s Earth-616, but the characters have been trapped in a pocket dimension with rewritten memories. Dr. James Bradley (aka Doctor Nemesis) was treating Legion, attempting to remove his alternate personalities. One of these personalities struck back, taking Moira’s face to taunt her former lover Xavier, and changing reality so Legion could finally be a hero instead of a problem child.

The setting isn’t a different slice of the multiverse, but a shared fantasy. The new backstories depicted in “Age of X: Alpha”? Never happened, they’re just fabricated memories, as were most of the 1000 days at Fortress X; Moira-Legion only created the new universe a week ago. Once “Moira” is defeated and Legion undoes her damage, the world is restored and the mutants regain their memories.

In the back notes of “X-Men: Legacy” #245, Carey compared writing “Age of X” to “playing a jazz riff on an existing song” due to how he had to reimagine familiar characters. I’d argue that sentiment applies to how he plays with the narrative too.

How Age of X compares to other X-Men multiverse stories

Carey told the Xavier Files that alternate timeline stories are part of the X-Men “DNA” and he would’ve felt “cheated” if he didn’t do one. “Age of X,” he admits, was mostly inspired by the 1995-1996 crossover “Age of Apocalypse.” In that story, Legion travels back in time to assassinate Magneto, but accidentally kills his father instead. This leads to a dystopian future where Apocalypse rules the world and Magneto leads the X-Men, who are named in honor of the late Charles. (Since they never had their falling out in this timeline, Magneto opted to continue his friend’s dream.)

The structure of “Age of X,” and Legion’s role in the story, definitely call to mind “Age of Apocalypse.” It also feels quite similar to 2005’s “House of M” (by Brian Michael Bendis and Olivier Coipel), where the Scarlet Witch rewrites reality to make mutants rulers of the world and gives everyone fake memories of this timeline’s history. In 2014, Carey wrote “X-Men: No More Humans,” a graphic novel drawn by Salvador Larroca, where every human on Earth vanishes and mutants have to find them (or decide if they even want to.) As Carey admitted on Xavier Files, the title is a reference to the signature moment in “House of M” — Wanda declares “No more mutants” and reduces the mutant population to less than 200. I wouldn’t be surprised if he was also thinking of “House of M” when writing “Age of X.”

MCU mini-series “WandaVision” drew on “House of M” and also focused on Wanda building a fantasy world to run from her pain. If the twist in “Age of X” sounds similar to “WandaVision,” that’s why.

Why so many X-Men stories involve alternate timelines

Besides “Days of Future Past” being an influential story, why do “X-Men” comics so frequently feature alternate timelines? Well, a core theme of “X-Men” is evolution — supposedly, one day mutants will supplant humanity and become Earth’s dominant species — and time is crucial to evolution.

The X-Men as we know exist at an inflection point, where mutants are on the rise but their ascendency is not guaranteed. Unless mutants grab power or win hearts and minds, humanity might end the mutant age in its infancy. Stories about dystopian futures show what happens if the X-Men fail while hate and fear retain their stranglehold on the world. Since the X-Men are a superhero brand first and foremost, they can’t advance in a way that the science-fiction side of their premise demands. Mutants will always be stuck in their position of marginalization. It’s foretold they will either advance or be wiped out, but neither outcome will every truly come to pass except in alternate timeline/multiverse stories where “canon” doesn’t matter.

Carey’s “X-Men” run is adept at understanding these themes. In his kick-off arc, “Supernovas” (“X-Men” #188-193), he and Chris Bachalo introduced a new group of villains: the Children of the Vault.

In the 1970s, a group of scientists became convinced that humanity would destroy itself and built a time capsule-like device that defied physics. This “Vault” held a whole city inside itself, a city where time moved much faster. The Children are the descendants of the humans who first entered the Vault; for them, millennia passed, not mere decades as it did for those outside the Vault. The Children have powers like mutants, but not the X-gene. Evolution means they’re no longer humans either; they are to us as we are to chimpanzees. Evolution, in the Darwinian sense, is a contest for survival among competing species. Carey escalates that war by introducing a new race to challenge the X-Men’s destiny as the heirs of tomorrow.

House of X/Powers of X recontextualized X-Men’s myriad multiverse

In 2019, writer Jonathan Hickman (with artists Pepe Larraz and R.B. Silva) changed “X-Men” forever with the interlocking mini-series “House of X/Powers of X.” This story featured mutant-kind colonizing the island nation Krakoa and becoming an overnight superpower; “X-Men” comics of this era are called the Krakoa era.

You can trace three pillars of past “X-Men” writers as Hickman’s primary influences. One, Chris Claremont (he wrote “X-Men” from 1975 to 1991, basically creating the book as it exists today, so every X-Men writer since is in conversation with him.) Two, Grant Morrison (who wrote a revolutionary run on “New X-Men” from 2001 to 2004). Three, Mike Carey. (Hickman told the Cerebro podcast that he was interested in having Carey be part of the X-Men writers room he built, but the scheduling stars didn’t align.)

For one, Hickman brought back the Children of the Vault as villains of his “X-Men” run. They were reintroduced as one of the primary threats to Krakoan dominance, and stayed as a recurring detail during the Krakoa era (capped off by Deniz Camp and Luca Maresca’s 2023 “Children of the Vault” mini-series.) Like in “Age of X,” Hickman also places Moira MacTaggert at the center of a conspiracy.

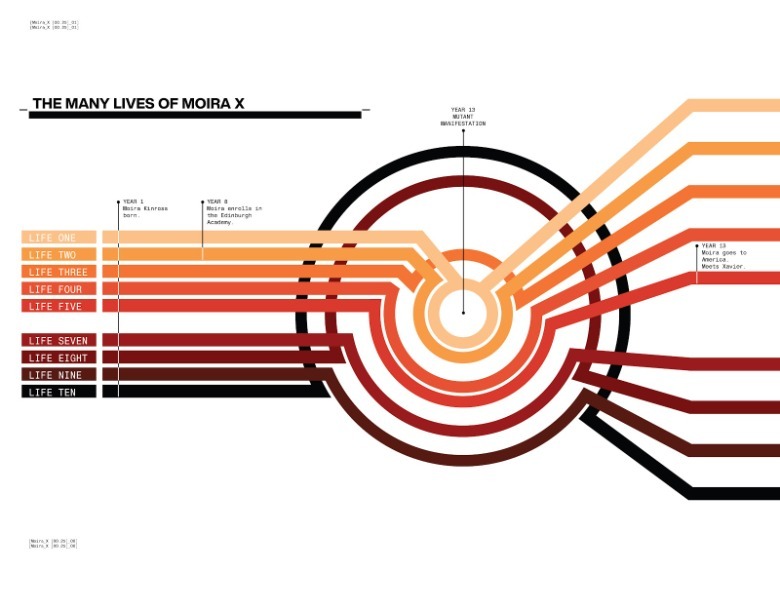

While “House of X” is mostly about the building of Krakoa, “Powers of X” reveals the seedy underbelly and a twist that recontextualizes everything. Moira is not a human, but a mutant with the gift of reincarnation. When she dies, the universe resets to the moment of her conception and she remembers everything.

How Moira MacTaggert reframed every X-Men story ever

The Marvel Universe of Earth-616? It’s Moira’s tenth life, and she’s seen mutants fall to humanity, artificial intelligence, and other threats in all her past nine lives.

Krakoa, built by Moira, Charles, and Magneto, is her latest attempt at survival. Like in “Age of X,” Moira also places a ban on mutants who can see past her veil. (In this case, clairvoyants who can see the future — Krakoa needs hope to sustain itself and if someone can tell mutants are doomed, it will collapse.)

Moira is like Hickman; she’s seen the X-Men fail many times, so it’s time to try something new. But her attempt at a mutant homeland, too, was destined to fail, even if mutant-kind didn’t have enemies who would work to see it so. Krakoa could never be a utopia. An ethnostate, even one built to shelter a persecuted minority, will always be built on the reactionary impulse to keep those who are different out. But despite these ethical contradictions Hickman loved exposing, Krakoa was definitely a step forward for storytelling. With its fall, X-Men comics have reverted to business as usual.

Moira alone gets her happy ending: an eleventh and final life where she can live and die like everyone else. In superhero comics, endings will always remain possibilities, which is why writers look outside “canon” to imagine them.