The secret to buying coffee you love means moving beyond the basics and understanding complex coffee labels. Buying roasted coffee is similar to wine in that the label contains a great deal of information — country or region of origin, how raw materials were processed, tasting notes — that contribute to the overall profile of the final product.

A coffee label will also detail any certifications for environmental standards or partnerships to regulate working conditions and compensation. Coffee certifications might seem straightforward but they can be the equivalent of greenwashing (looking at you Rainforest Alliance) if you don’t know what you’re looking for.

We’re breaking down the elements of coffee labels to demystify both specialty and grocery store brands alike, which can also be used as a guide for purchasing ethical or more environmentally friendly options. Plus, you’ll know how to avoid paying more for labels with dubious claims.

We will break down certifications such as Fairtrade versus direct trade, as well as explain what all the information on a label means, including the difference between origin and local roasters, single-origin, types of beans and roasts.

Type of Bean

Most coffee produced is either arabica or robusta.

There are over 120 species of coffee beans, but all commercial beans will be one of four varieties: arabica, robusta, liberica and excelsa. The reality is arabica accounts for the majority of coffee sold across the world with robusta in a much lower second place.

Due to rising costs, climate change, and renewed interest in lesser-known varieties, specialty coffee beans made from liberica and excelsa are once again gaining traction outside of Southeast Asia and East Africa.

A blend of coffee beans can achieve particular tasting notes or caffeine content, but it can also mask beans with a less-than-ideal flavor profile.

Robusta vs Arabica

| Robusta | Arabica | |

|---|---|---|

| Percent of coffee sold | 60-70% | 30-40% |

| Caffeine | 1.7-4% | 0.8%-1.4% |

| Altitude grown | Lower | Higher |

| Sugars | 3-7% | 6-9% |

| Lipids | Less | More |

Arabica

Arabica beans account for the vast majority of beans grown and roasted around the world. The plant originated in Ethiopia but Brazil is the largest exporter. Arabica’s popularity is partly due to what is considered a sweeter and less acidic flavor profile. The delicate and disease-prone arabica beans are grown in cool temperatures and higher elevations, around 3,000 to 6,000 feet, resulting in slower growth but more complex flavors.

The bean thrives in tropical climates typically around the equator and several genetic varieties are found in Colombia, Indonesia, Guatemala, India and Vietnam. Some claim the delicate flavors can be too mild to stand up in iced coffee, but seeing Starbucks uses arabica beans exclusively, this really comes down to roast rather than the bean.

Robusta

As the second most common bean used for commercial coffee, robusta is likely one you’re familiar with even if you don’t realize it. This bean is disease resistant, which helps make robusta cheaper to grow, so it tends to be used in instant coffee or cheaper brands. Robusta also has a higher caffeine content than arabica beans, and it’s often used as part of a blend to make espresso.

The coffee is often criticized for its burnt or rubbery taste when of low quality. Robusta can shine with notes of rum or chocolate when made from single-origin beans and in smaller batches. Kisansa is a native variety of robusta in Uganda growing in the market, while Vietnam produces the most robusta beans in the world. You can find high-end varieties sourced from Brazil, India and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Despite hundreds of varities, two types of coffee beans dominate the global market.

Liberica

Native to Liberia, the liberica coffee bean is growing again in popularity thanks to its resistance to disease. Liberica coffee dominated the global market in the 1890s when arabica beans experienced widespread coffee leaf rust. The species is known for larger beans with thick skin, attributes that make the beans more intensive to process and have therefore slowed more widespread production.

Liverica beans are known for their smooth and sweet flavor, which can be less appealing or “vegetal” if not processed and roasted correctly. The Philippine Islands produce a large amount of liberica coffee, where it is called barako, with small producers across Southeast Asia, especially Malaysia and West Africa.

Excelsa

Excelsa coffee beans are a variety of liberica but are different enough to warrant their own category. Excelsa is seeing increased production in countries such as Uganda and South Sudan where the plant is indigenous. The coffee flavor is considered mild with berry notes, low acidity and less bitterness than liberica coffee. It’s also often mixed with robusta or arabica beans for export.

Roast Level

How long the coffee is roasted affects the end flavor dramatically.

Coffee’s roast level is one of the biggest factors in the overall flavor of coffee. The same beans will taste vastly different if lightly roasted versus roasted for longer to reach the dark roast categorization. Roasting coffee is a spectrum, but light or dark roasts are the standard across the industry.

Light roast

Light roast coffee beans are exposed to less heat, which causes moisture to evaporate and oils to release. Lighter roasts often retain more complex and fruit-forward flavors. The beans retain their weight but produce a thinner coffee when brewed. Ignore myths that claim light roast has more caffeine than dark roasts as a result of less exposure to heat. Studies show roasting has little to no effect on coffee’s caffeine content.

Lighter roasts tend to exhibit more nuanced and fruit-forward flavors while darker roasts offer a rich and toasty profile.

Dark roast

Darker roasts tend to result in toasted notes and more full-bodied flavors like caramel. More oils are released from the longer roast, so the coffee will be thicker when brewed. Dark roasts also tend to contain more bitterness and more robust overall. Darker roast beans also weigh less because more moisture is evaporated when processed longer, so if you measure coffee by weight rather than by scoops, a dark roast will contain more beans, and therefore more caffeine, than a cup of light roast as a result.

Espresso beans are often dark roasted for a more robust flavor when mixed with milk. Despite many brands selling an “espresso roast,” the term “espresso” refers to how coffee is brewed, not a specific roast.

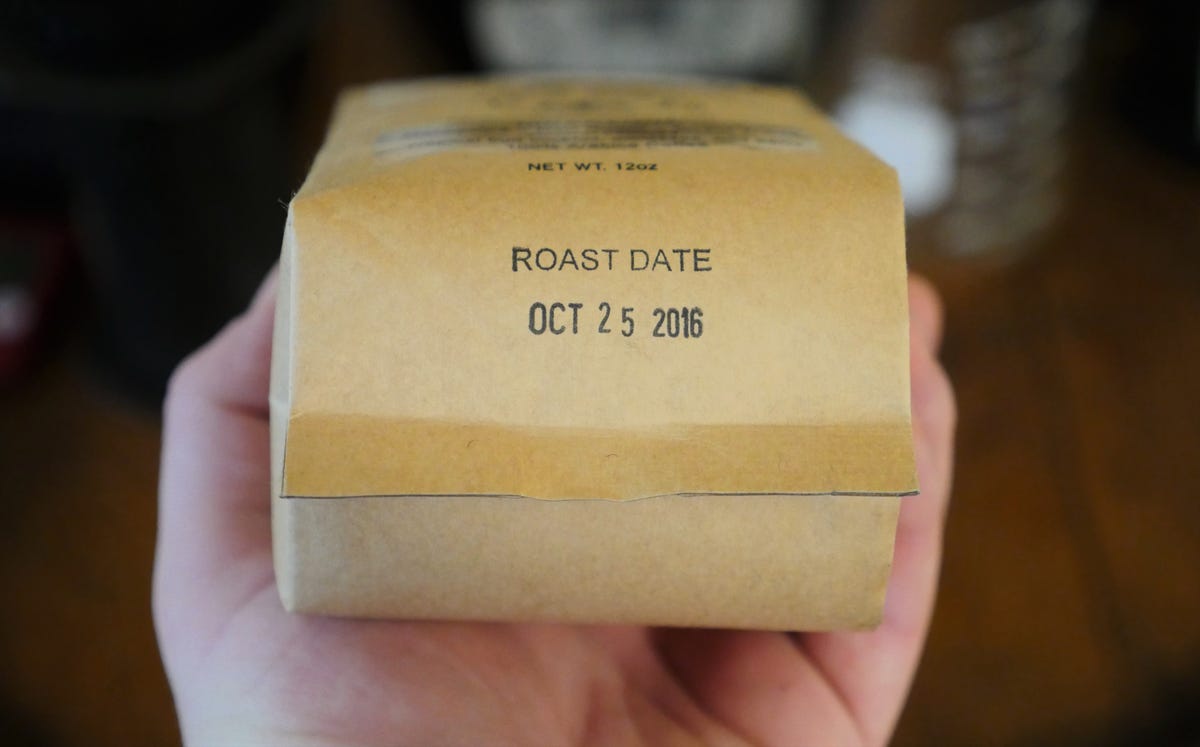

Roast date

Pay attention to the roast date. It will signal how fresh the beans inside are.

The roast date is becoming more common on coffee labels instead of a “best buy” date because it isn’t a great indicator of freshness. The best-buy date could mean it was roasted many months prior. Popular opinion says that coffee should be consumed seven days to three weeks after roasting to catch flavors at their peak. Unless you buy straight from a roaster, even specialty coffees won’t reach store shelves within that timeframe.

In reality, the roast plays a big factor in oxidation, which causes the coffee flavors to turn stale. Dark roasts can turn rancid due to the additional oils. More commonly, old coffee will be less vibrant but still taste fine. Light roasts can stay tasty for up to two months when stored properly.

Roasted at origin

Roasted-at-origin coffees are gaining notoriety for roasting fresh beans within the same country or region where the beans are grown. Local processing often means a shorter supply chain, as in fewer stops along the way before it reaches your cup, because the uncooked coffee cherries aren’t sitting in transit for weeks or months waiting to be delivered to a roaster in another country. Coffee isn’t typically consumed until at least one week after the beans are roasted to allow for transport time.

The flavors of the terroir can be preserved and local growers benefit from the increased profits of specialty roasting that is otherwise reserved for intermediaries or the country of import. (Buying “local” coffee in Colorado or New York is more of a marketing tool than a model of sustainability when beans are first imported from Kenya or Brazil.) The idea is that farmer roasters are also able to increase traceability and ensure quality control.

Single origin

Single-origin coffee is often more expensive than other specialty coffees but drinking it can help you develop a taste for terroir.

Single-origin beans are sourced from one farm, cooperative or in-farm mill. Single-origin is the opportunity to become familiar with the terroir of a region, as in the taste derived from environmental elements like minerals in the soil and the groundwater. The major appeal for enthusiasts is how single-origin beans can result in flavor profiles, acidity levels, textures and aromas that are specific to a time and place, similar elements you might seek out in a single-vineyard wine or single-malt Scotch.

Like its alcoholic counterparts, single-origin coffee is often more expensive than other specialty coffees that source beans from multiple growers or regions. Coffee sourced from one region or grower doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s better-tasting coffee. An added benefit is that it’s also easier for traceability to prove that the beans are grown and processed according to the brand’s claims, whether it’s organic, fresh or ethically produced. It’s also an approach that goes in and out of popularity.

Processing method

Certain regions have specialized approaches to cleaning and drying coffee cherries that highlight its distinct characteristics.

Coffee cherries are processed in a variety of traditional and modern methods to strip the skin and pulp from the seed. The roasted seeds are the coffee beans we know and consume en masse. Processing methods historically are in response to the local climate or the farm’s access to water. Individual countries have developed specialized approaches to cleaning and drying the beans that highlight and preserve distinct characteristics. Processing comes down to personal preference and is an opportunity to sample a range of approaches to find one you prefer.

Washed process

Wet processing has become more widespread for the sake of consistency and preservation of the flavors of the bean. Washed coffee is also said to preserve acidity or brightness. Coffee cherries are sorted based on whether they sink or float, the skin is then removed and are left in water for around 24 hours to a couple of days. This allows them to ferment with the mucilage, the fruit pulp, that clings to the coffee seeds. The seeds (or coffee beans) are then rinsed and dried in a machine or outdoors, depending on the local climate.

Hybrid models are also used. Kenya producers are known for using a longer fermentation period and subsequent soak (sometimes more than once) to clean the beans, called double washed or double fermentation. The beans are left to dry on raised beds in the often sunny and dry climate. The method allows for a brighter acidity, fruit flavors and vibrant tasting notes.

Dry process

Also called the natural process, dry-washed coffee is one of the most traditional methods that started in locations with dry climates and little access to water. Cherries are separated by winnowing, or separating the cherreis, either by hand with a sieve or with a machine. The full cherries are dried naturally in the sun, then raked and turned during the day to further dryer. Once complete the beans are either stored or hulled to remove the outer skin and inner layers. The contact with the skin and pulp for greater duration results in a smooth and heartier flavor.

Hybrid processes

The wet and dry methods are combined for natural washed technique, called honey. The skin is removed with water then the seeds are laid out to dry with the pulp still attached. The honey process is performed in countries such as Brazil and Costa Rica where specialty producers often experiment with how much pulp is left on the seeds, resulting in full-bodied beans with a lower acidity but less of the fruit-forward notes.

Sumatra coffee features earthy notes in part because of a method called giling basah or wet hulling. The skin and pulp are left on the coffee seeds to offer plenty of body and low acidity, but the drying process is interrupted to hull the seeds after one or two days. The seeds are pliable and moist, in contrast to the standard of hulling the beans once fully dried. The beans might be misshapen by comparison, but the method enhances the final tasting notes of cured tobacco.

Coffee certifications

Fairtrade

The Fairtrade certification appears on a range of agricultural products, including coffee. Fairtrade International is a nonprofit organization that oversees trade standards between buyers and producers, making sure farmers are paid a minimum price to cover the cost of what they grow. That might seem like an obvious standard, but it’s common for buyers across industries to negotiate the cheapest prices for products and services resulting in lower wages — think textiles for fast fashion or cocoa to make chocolate.

When you see a Fairtrade label (spelled Fair Trade by the U.S. branch) on a bag of coffee, it signifies not only a price minimum for what farmers are compensated for the beans but requirements for exporters, brokers and companies along the supply chain. The Fairtrade certification comes with a complex set of rules for environmental protections, such as safe disposal of agricultural waste, and labor standards prohibiting child or forced labor. As a result, Fairtrade coffee often costs more to offset the costs.

Direct trade

Direct trade is a more recent logo found on coffee labels designed with similar intentions to Fairtrade certification. Major coffee producers devised the label as an alternative trade model without the verification process. In some ways, direct trade could be compared to the Better Business Bureau since standards are not enforced and any association is more symbolic of a company’s intentions. Or think of direct trade as the ride-share model meant to disrupt the costly hurdles imposed on taxi drivers.

The idea is personalized pricing between farmers and buyers to develop more realistic pricing and long-term relationships. Proponents say rather than receiving a set Fairtrade price, farmers in microclimates with sought-after beans are incentivized by a premium when a bean or process might require more time or cost investment.

Rainforest Alliance

The Rainforest Alliance is a certification best recognized by a cute little frog logo found on coffee or chocolate packaging. Unfortunately, due to careful wording and a history of dubious sourcing, the label doesn’t stand for much in terms of ethics or sustainability. The Rainforest Alliance has courted controversy due to several lawsuits over the years, such as a class action lawsuit filed in 2024 claiming the organization made false claims and forged audit documents about child labor, worker conditions and deforestation. The alliance even merged with the UTZ company, which has a history of providing cocoa produced using child labor.

Traceability is so important since major retailers use the logo — and pay the Rainforest Alliance a percentage of sales to do so – have no idea what working conditions are like when sourcing from countries with child labor and harmful deforestation practices. This label might best be described as the definition of “greenwashing,” but (thanks to our careful wording) let the lawsuits speak for themselves.

Coffee labels FAQ

Is Fairtrade coffee worth it?

The Fairtrade certification is similar to “organic” foods in that farmers must meet specific standards that are verified for the symbol to appear on a label. The reality is the certification is not a panacea for better wages or labor conditions. Researchers have shown Fairtrade standards have benefited small farmers in places like West Africa. Other studies have found that hired workers are often paid the same regardless of higher prices, and food insecurity is still an issue.

The cost of obtaining and maintaining the certification is also steep, which cuts into the profits for producers and strains time and resources. One study shows certified producers in Nicaragua are often poorer than other farmers. Regulations only state that wages must comply with legal requirements. Although the Fairtrade label is one of the most regulated coffee certifications, it appears that more work can be done.

How is Fair Trade different than direct trade?

Fairtrade certification is regulated with the aim of maintaining standards of compensation, sustainability and ethical working conditions. Direct trade is a set of guidelines where businesses commit to standards, such as buying from local farmers and providing sustainability reports.

The benefit of the direct trade label is that it’s not a costly certification with a greater onus on farmers and buyers can work with growers based on specific needs rather than a set minimum. Without third-party oversight, it’s up to the buyers to report what constitutes “preferential” payment.

Major coffee brands, such as Stumptown Coffee, claim its direct trade standards include paying higher prices for goods and traceability by working with reliable producers. It’s similar to how “natural” is used on products instead of a regulated “organic” label. Any brand can claim its product is “natural” because it has no government regulations, but it evokes a similar connotation for buyers.